Mudgee

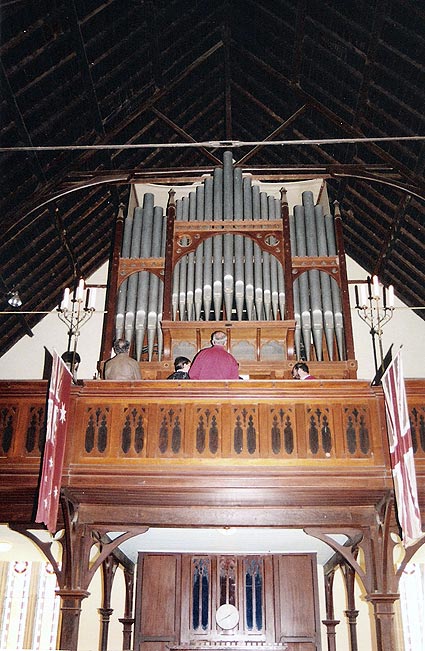

1881 Brindley & Foster, Sheffield,

Res. 1966 S.T. Noad & Son,

Res. 2008 Peter D.G. Jewkes Pty Ltd. 3m., 24 sp.st., 5c., tr

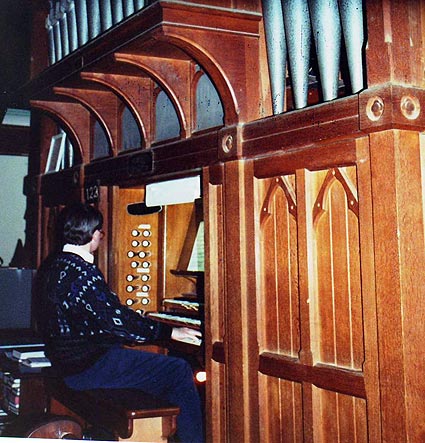

Photo: Trevor Bunning (1990)

Photo: Rodney Ford (July 2007 before being dismantled for restoration)

From the 2010 OHTA Conference Book, Dr Kelvin Hastie writes:

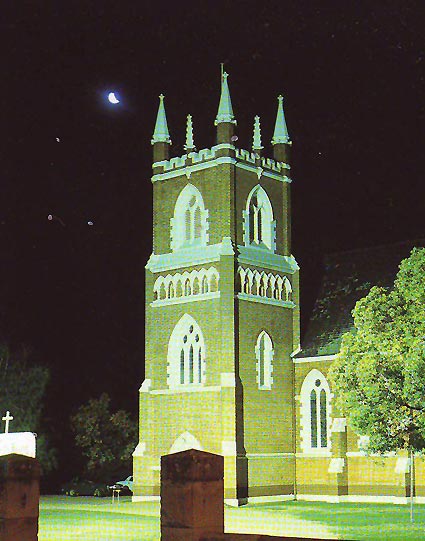

The principal attraction of Mudgee today is its fine collection of heritage sites, including commercial and civic buildings, churches and public homes. The Anglican and Catholic Churches face one another across the main intersection of the town and provide magnificent points of focus to the streetscape. Both are imposing neo-gothic stone structures with towers. The town is surrounded by productive farmlands; cattle and horse breeding together with viticulture are especially successful. Located away from the principal road and rail routes, Mudgee has been able to retain its essential heritage qualities free from the excesses of crass overdevelopment. It is also adjacent to some magnificent large tracts of wilderness.

The foundation stone of St John’s was laid in 1853 by Bishop Barker and by 1860 the nave, chancel and vestry had been completed to the design of architects Weaver & Kemp, of Sydney, the builder being James Atkinson. In 1870 a western gallery and tower were added in accordance with the original design, the latter being richly decorated with Gothic openings and pinnacles. Constructed in tuck-pointed brickwork with stone dressings (later painted white), the style of the church is Decorated Gothic, with large east and west windows. Internally the plastered walls incorporate many fine stained glass windows and there are fine and original furnishings in the Gothic style.

The discovery of gold in the region caused tremendous growth in the period following 1850 and the previous church building constructed in 1841 became too small. An organ supplied to the church by J.W. Walker in 1855 was given to the Mudgee Presbyterians in 1882. This followed the installation from Sheffield of the Brindley & Foster organ, currently in use. [52]

The Brindley & Foster organ, with 3 manuals, 24 speaking stops and tracker action throughout, is one of the finest examples of nineteenth century British organ building in New South Wales. It was built in 1881 as a gift to the church by Mr Robert White whose name is associated with several other organs installed in New South Wales in this period. The instrument was tested by Sir John Stainer who made an inspection of it in the Sheffield works of the firm. [53]

The organ remained unaltered until 1941 when an overhaul was undertaken and tuning slides fitted to most of the metal pipes. In spite of this work it was reported in the early 1960s that a major rebuild would be necessary. In 1963 two eminent organists, Mervyn Byers (of St Andrew's Cathedral, Sydney) and Dr Gerald Knight (of the RSCM in England) recommended that the organ be fully electrified with the provision of a detached console. A contract for this work had been let to S.T. Noad & Son. However, at the last minute, David Kinsela was able to persuade the rector, The Revd. Graham Walden, his church wardens and the Parish Council, to abandon this scheme in favour of restoration. This was a courageous move, given that Noad had already ordered many of the electric action components for the rebuild. Noad subsequently carried out the restoration of the organ under David Kinsela's supervision. Although the cost factors were important in reversing the decision (about £3,000 was saved), this was one of the earliest examples of direct action to secure the preservation of an historic organ in New South Wales. [54]

The fitting of tuning slides, the alteration of the bellows from double to single rise and the removal of the hand blowing apparatus are the only changes to have been carried out on the organ. The organ retains its original console fittings, a magnificent case with a full set of spotted metal pipes, its original action, soundboards and pipework. [55]

In 2007 St John’s received a grant of $50,000 from the NSW Heritage Office to assist the further restoration of the organ. This was part of the church’s 165th anniversary celebrations. The work was undertaken by Peter D. J. Jewkes Pty Ltd and the consultant was the church organist, Gavin Tipping. The organ was rededicated by The Bishop of Bathurst, The Revd Richard Hurford OAM, on 31 August 2008, with organists Gavin Tipping, The Revd Michael Deasey and Peter Jewkes presiding at the console.

To mark the completion of the restoration project, Peter Jewkes wrote the following article (“Restoring the Restored”, Sydney Organ Journal, 39/3 (Spring 2008): 44-46), slightly abridged below:

“David Kinsela’s timely intervention, and the ensuing 1966 restoration of the Mudgee organ, were watersheds in the world of organ conservation, and probably the first work of its kind in Australia. Prior to that time the standard treatment for 19th century instruments in NSW was a quick cleaning and overhaul which was probably all that was required, given their typical age of perhaps only 70 years. In Victoria such organs were likely to have been electrified with the presence of two or three large “electric action” firms in Melbourne a serious temptation. Possibly due to lack of available funds and the limited number of organbuilders at work in NSW a surprisingly large number of organs escaped more or less intact. On a per capita basis NSW can probably boast a higher percentage of preserved Victorian organs than most other parts of the Western world. . . .

From our observations during the present restoration, confirmed by conversation with David Kinsela, the only modifications in 1966 appeared to have been:

1. The alteration of the large bellows to single-rise design

2. The introduction of several sets of wire trackers into the action

3. Provision of a new Tremulant

4. The use of plastic glue in the soundboard restoration and the fitting of larger pallets to the bottom sixteen notes of the Swell and Great soundboards

5. The refacing of the keyboards with poorly fitting white plastic

Each of these modifications had a deleterious effect on the organ – for example the character of the wind system, and an unpleasantly “springy” key touch caused by the pluck from the new large pallets and exacerbated by the stretching wire trackers. None of them however constituted a serious breach of its historical integrity, and given the hitherto unique nature of the project, it was pleasing to find so much of the organ’s character intact. The poor condition in which we found the instrument during our first inspection in 2005 was mostly attributable to the lack of any major work on it (such as routine cleaning) since 1966, wear and tear, and the horrendous climatic extremes experienced in a gallery situation in Central West NSW – temperature fluctuations of over 15 degrees Celsius in one day in our experience, and over 35 degrees in a year.

Work therefore proceeded along more or less standard lines, in accordance with our own conservation philosophy as well as NSW Heritage: Pipe Organ Conservation and Maintenance Guide (Sydney: NSW Heritage Office and the Organ Historical Trust of Australia, 1998). The opportunity was also taken to reverse the few infelicitous alterations.

The action was thoroughly restored and refurbished throughout. New wooden trackers were fitted to replace wire ones.

The soundboards were completely restored and re-palleted. Unfortunately, due to the presence of PVA glue used in 1966, the “flooding” normally done with a traditional hot glue mixture had to be undertaken with more PVA glue. The large numbers of cracks and splits in the soundboard tables were carefully screwed, pegged and filled. The new over-large pallets were retained to ensure good wind supply to the bass notes, but were re-shaped to ameliorate the unpleasant “pluck” in the key action. The soundboards had evidently been unsatisfactory for some time, with sundry murmurs and runnings, and there were copious bleed holes drilled through the bar ends, and even more drilled into pipe feet. These have now all been filled, necessitating extra attention during tonal finishing of the affected pipes, found to be over-blowing when restored to their full wind supply (having no doubt been loudened originally to compensate for the loss of wind through the bleed holes!)

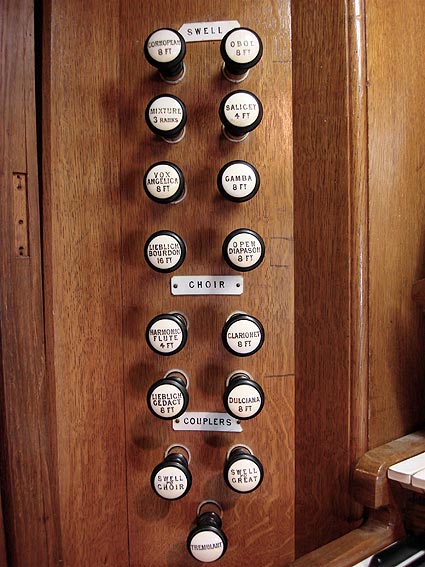

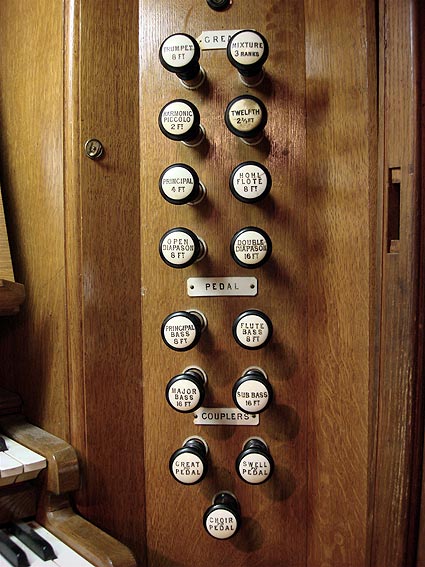

The console was restored, with the 1966 white felt drawstop bushings replaced with traditional burgundy felt. The keys were returned to our English keymakers for recovering with ivory resin, and now present a far better “cosmetic” appearance. The pedalboard was well re-faced in 1966 and needed only basic re-felting, cleaning and waxing. Numerous extraneous ugly fittings were removed, holes in the timberwork were carefully filled with matching English oak, and new discreet mirrors and light fittings were provided. A new brass tell-tale was fitted to the original pulley, replacing one long since removed. The polish work was waxed and freshened, without alteration of the original patina. New ivory resin department labels were fitted, copied from what remained of the old ones (all broken and partly missing).

The bellows was returned to its original double-rise design, with new ribs and centre frame manufactured from the well-seasoned hoop pine. Happily, the original metal counter-balances were discovered under the gallery floor while the organ was being removed, and so were restored and re-fitted. The remaining wind system was re-gasketted and restored.

The pipework was cleaned and restored with the tuning stoppers of wooden pipes re-leathered, metal pipes carefully rounded out and repaired. An unexpectedly large amount of time was devoted to making permanent the myriad repairs of split wooden pipes. The stopped metal pipes were tuned with a very motley assortment of cork bungs, screws and stop knobs, aided and abetted by liberal application of blue insulating tape. As it is virtually impossible to procure good quality cork (witness the rise of the Stelvin Closure for wine bottles) these were sent to our Melbourne pipemakers to have felted metal tuning canisters fitted – the improvement in tuning stability was immediately obvious on their return. The reed pipes were also renovated in Melbourne.

Re-assembly of the organ was completed in May, to ensure the organ qualified for its grant from the NSW Heritage Council. The very unusual horse hair and fibre panels of the Swell box were sealed, and the beautifully engineered vertical Swell shutter action restored. The casework was cleaned and wax polished, and the original concussion bellows reinstated. It is hoped that these items will be restored in the not too distant future when funds allow, along with the provision of a new traditional Tremulant. While the organ was being re-installed, the opportunity was also taken by the church to carry out some “housekeeping” in the gallery, including providing superior insulation of the West window behind the organ and planning for improved ventilation – both of which are hoped will protect the organ from the gallery’s extremes of temperature.

Tonal finishing and on-site voicing was carried out by the writer with meticulous care taken to preserve what was clearly still the original tonal qualities of the organ. No changes were made to the overall tonal balances, with only basic regulation undertaken, and attention to numerous notes off-speech. The wind pressure was said to have been raised by a visiting organbuilder shortly before our first inspection of the instrument, confirmed by the presence of a number of clean new bricks on the bellows. As measured at dismantling it was 3 inches – too high for the pipework with its low cut-ups, resulting in a great deal of unmusical “barking” from the fluework. The organ’s already sharp pitch was also raised even further as a result. The re-instatement of the double-rise bellows and the use of only the original bellows weights instantly solved these problems, with a working pressure of exactly 3 inches and pitch of a = 447 Hz @ 20°.

Many questions were raised in the course of this part of the project. Why was the work of Sheffield’s Brindley & Foster said to be so heavily influenced by that of Edmund Schulze in Yorkshire? Even the briefest inspection of Schulze’s arresting tonal work at Armley or Doncaster would reveal few if any similarities to the gentle under-blown sounds of the Brindley & Fosters at Mudgee or Cook’s River. Why did the otherwise sensible specification at Mudgee include the luxury of two manual 16’ stops, but no Swell 8’ Flute? Certainly the well engineered layout and construction of the organ and its metric measurements, owe much to the firm’s German employees, but the same cannot be said for its tone.

And perhaps most confusing of all, why was the sole 2’ stop on the organ a Great Piccolo, and what registrations were expected of it? Surely not the faux-Baroque 8’ Flute and 2’ Piccolo, much loved in the 1970s? Was it seen as a legitimate chorus stop, or was it purely for effect, with the expectation that the Mixture (which contains a Fifteenth throughout its compass) would carry the chorus? An answer has yet to be found.

Finally the question of the Great Twelfth having replaced a Dulciana was laid to rest. Whilst the pipes were clearly of Dulciana scale and tone, and some were in fact marked “DUL”, this had obviously always been so, and the Dulciana pipes were used from the time the organ was built, presumably being surplus to requirements in the Sheffield factory in 1881. The musical result is actually a very attractive stop, working well in chorus or providing solo colour.

Only posterity will tell how successfully we have succeeded in attempting to be faithful to the thinking and creativity of the original builders. With regular maintenance it is hoped that this restoration will outlast Noad’s work of 1966, but it is still to the foresight of those responsible for this work that we owe the privilege of being able to attend to the organ in these hopefully more conservation-enlightened days.”

The specification, noted in 1981 by John Stiller, is:

Brindley & Foster 1881 (3/24 mechanical)

Great |

16 Ft. 8 Ft. 8 Ft. 4 Ft. 2-2/3 Ft. 2 Ft. 3 ranks 8 Ft. 16 Ft. 8 Ft. 8 Ft. 8 Ft. 4 Ft. 3 ranks 8 Ft. 8 Ft. 8 Ft. 8 Ft. 4 Ft. 8 Ft. 16 Ft. 16 Ft. 8 Ft. 8 Ft. |

* + [t.c.] # A A |

Couplers

Swell to Great

Swell to Choir

Great to Pedal

Swell to Pedal

Choir to Pedal

Mechanical action throughout

Compass 58/30

5 composition pedals

Hitch-down swell Pedal

Number of pipes = 1,459

Composition of both Great and Swell Mixture 3 ranks

C – e0: 15.19.22

f 0 – e1: 12.15.19

f 1 – a3: 8.12.15

* C – F# from Open Diapason

+ From d0

# C- B from Lieblich Gedact

52 Rushworth, Historic Organs, pp. 226-27.

53 ibid., 227

54 Notes supplied by David Kinsela to Kelvin Hastie, 1979.

55 John Stiller, “Documentation of Pipe Organ built by Brindley & Foster 1881 - St John the Baptist Anglican Church, Mudgee NSW”. Organ Historical Trust of Australia, 9 June 1981.

From the Spring 2008 SOJ:

RESTORING THE RESTORED?

From the organbuilder, Peter Jewkes

David Kinsela’s timely intervention, and the ensuing 1966 restoration of the Mudgee organ, were watersheds in the world of organ conservation, and probably the first work of its kind in Australia. Prior to that time the standard treatment for 19th century instruments in NSW was a quick cleaning and overhaul which was probably all that was required, given their typical age of perhaps only 70 years. In Victoria such organs were likely to have been electrified with the presence of 2 or 3 large “electric action” firms in Melbourne a serious temptation. Possibly due to lack of available funds and the limited number of organbuilders at work in NSW a surprisingly large number of organs escaped more or less intact. On a per capita basis NSW can probably boast a higher percentage of preserved Victorian organs than most other parts of the Western world.

It was regrettable therefore that the largest of the three Brindley and Foster organs exported to the colony, at Bathurst Cathedral, was enlarged and altered several times, with its action being electrified in 1964. This of course made the pioneering preservation of the slightly smaller instrument at Mudgee even more worthwhile, and thanks are due not only to this heroic work, but to the church itself for “heeding the call”, and indeed (according to David Kinsela) to the graciousness with which S. T. Noad & Son were prepared to relinquish the contract signed with them to electrify the organ. It is amusing to note the use of components imported for the electric action, such as the drawstops (peculiarly engraved with the Mudgee stop names and therefore inappropriate elsewhere) recycled in other Noad instruments of the period!

Popular anecdotal history has attributed a variety of alterations to the 1966 restoration, such as replacement of the pedalboard and transposition of a Great Dulciana, but this is in fact inaccurate. From our observations during the present restoration, confirmed by conversation with David Kinsela, the only modifications in 1966 appeared to have been:

the alteration of the large bellows to single-rise design,

the introduction of several sets of wire trackers into the action,

provision of a new Tremulant,

the use of plastic glue in the soundboard restoration and the fitting of larger pallets to the bottom 16 notes of the Swell and Great soundboards,

the refacing of the keyboards with poorly fitting white plastic.

Each of these modifications had a deleterious effect on the organ – for example the character of the wind system, and an unpleasantly “springy” key touch caused by the pluck from the new large pallets and exacerbated by the stretching wire trackers. None of them however constituted a serious breach of its historical integrity, and given the hitherto unique nature of the project, it was pleasing to find so much of the organ’s character intact. The poor condition in which we found the instrument during our first inspection in 2005 was mostly attributable to the lack of any major work on it (such as routine cleaning) since 1966, wear and tear, and the horrendous climatic extremes experienced in a gallery situation in Central West NSW – temperature fluctuations of over 15 degrees Celsius in one day in our experience, and over 35 degrees in a year.

THE RESTORATION

Work therefore proceeded along more or less standard lines, in accordance with our own conservation philosophy as well as NSW Heritage: Pipe Organ Conservation and Maintenance Guide (Sydney: NSW Heritage Office and the Organ Historical Trust of Australia, 1998). The opportunity was also taken to reverse the few infelicitous alterations.

The action was thoroughly restored and refurbished throughout. New wooden trackers were fitted to replace wire ones.

The soundboards were completely restored and re-palleted. Unfortunately, due to the presence of PVA glue used in 1966, the “flooding” normally done with a traditional hot glue mixture had to be undertaken with more PVA glue. The large numbers of cracks and splits in the soundboard tables were carefully screwed, pegged and filled. The new over-large pallets were retained to ensure good wind supply to the bass notes, but were re-shaped to ameliorate the unpleasant “pluck” in the key action. The soundboards had evidently been unsatisfactory for some time, with sundry murmurs and runnings, and there were copious bleed holes drilled through the bar ends, and even more drilled into pipe feet. These have now all been filled, necessitating extra attention during tonal finishing of the affected pipes, found to be over-blowing when restored to their full wind supply (having no doubt been loudened originally to compensate for the loss of wind through the bleed holes!)

The console was restored, with the 1966 white felt drawstop bushings replaced with traditional burgundy felt. The keys were returned to our English keymakers for recovering with ivory resin, and now present a far better “cosmetic” appearance. The pedalboard was well re-faced in 1966 and needed only basic re-felting, cleaning and waxing. Numerous extraneous ugly fittings were removed, holes in the timberwork were carefully filled with matching English oak, and new discreet mirrors and light fittings were provided. A new brass tell-tale was fitted to the original pulley, replacing one long since removed. The polish work was waxed and freshened, without alteration of the original patina. New ivory resin department labels were fitted, copied from what remained of the old ones (all broken and partly missing).

The bellows was returned to its original double-rise design, with new ribs and centre frame manufactured from the well-seasoned hoop pine. Happily the original metal counter-balances were discovered under the gallery floor while the organ was being removed, and so were restored and re-fitted. The remaining wind system was re-gasketted and restored.

The pipework was cleaned and restored with the tuning stoppers of wooden pipes re-leathered, metal pipes carefully rounded out and repaired. An unexpectedly large amount of time was devoted to making permanent the myriad repairs of split wooden pipes. The stopped metal pipes were tuned with a very motley assortment of cork bungs, screws and stop knobs, aided and abetted by liberal application of blue insulating tape. As it is virtually impossible to procure good quality cork (witness the rise of the Stelvin Closure for wine bottles) these were sent to our Melbourne pipemakers to have felted metal tuning canisters fitted – the improvement in tuning stability was immediately obvious on their return. The reed pipes were also renovated in Melbourne.

Re-assembly of the organ was completed in May, to ensure the organ qualified for its grant from the NSW Heritage Council. The very unusual horse hair and fibre panels of the Swell box were sealed, and the beautifully engineered vertical Swell shutter action restored. The casework was cleaned and wax polished, and the original concussion bellows reinstated. It is hoped that these items will be restored in the not too distant future when funds allow, along with the provision of a new traditional Tremulant. While the organ was being re-installed, the opportunity was also taken by the church to carry out some “housekeeping” in the gallery, including providing superior insulation of the West window behind the organ and planning for improved ventilation – both of which are hoped will protect the organ from the gallery’s extremes of temperature.

Tonal finishing and on-site voicing was carried out by the writer with meticulous care taken to preserve what was clearly still the original tonal qualities of the organ. No changes were made to the overall tonal balances, with only basic regulation undertaken, and attention to numerous notes off-speech. The wind pressure was said to have been raised by a visiting organbuilder shortly before our first inspection of the instrument, confirmed by the presence of a number of clean new bricks on the bellows. As measured at dismantling it was 3 ins – too high for the pipework with its low cut-ups, resulting in a great deal of unmusical “barking” from the fluework. The organ’s already sharp pitch was also raised even further as a result. The re-instatement of the double-rise bellows and the use of only the original bellows weights instantly solved these problems, with a working pressure of exactly 3 ins and pitch of A = 447 Hz @ 20°.

Many questions were raised in the course of this part of the project. Why was the work of Sheffield’s Brindley & Foster said to be so heavily influenced by that of Edmund Schulze in Yorkshire? Even the briefest inspection of Schulze’s arresting tonal work at Armley or Doncaster would reveal few if any similarities to the gentle under-blown sounds of the Brindley & Fosters at Mudgee or Cook’s River. Why did the otherwise sensible specification at Mudgee include the luxury of two manual 16’ stops, but no Swell 8’ Flute? Certainly the well engineered layout and construction of the organ and its metric measurements, owe much to the firm’s German employees, but the same cannot be said for its tone.

And perhaps most confusing of all, why was the sole 2’ stop on the organ a Great Piccolo, and what registrations were expected of it? Surely not the faux-Baroque 8’ Flute and 2’ Piccolo, much loved in the 1970s? Was it seen as a legitimate chorus stop, or was it purely for effect, with the expectation that the Mixture (which contains a Fifteenth throughout its compass) would carry the chorus? An answer has yet to be found.

Finally the question of the Great Twelfth having replaced a Dulciana was laid to rest. Whilst the pipes were clearly of Dulciana scale and tone, and some were in fact marked “DUL”, this had obviously always been so, and the Dulciana pipes were used from the time the organ was built, presumably being surplus to requirements in the Sheffield factory in 1881. The musical result is actually a very attractive stop, working well in chorus or providing solo colour.

THE CONCLUSION

A project of this duration, size and time constraint obviously involves a team effort. Our staff members Murray Allan, Nick Appleton, Rodney Ford, Peter Jewkes, Julie McLauchlan, David Morrison and Joshua Swann attended to the vast amount of “in house” work. Specialist subcontractors Australian Pipe Organs, Tim Gilley, Darrell Pitchford and Peter Clark also provided valuable assistance.

Only posterity will tell how successfully we have succeeded in attempting to be faithful to the thinking and creativity of the original builders. With regular maintenance it is hoped that this restoration will outlast Noad’s work of 1966, but it is still to the foresight of those responsible for this work that we owe the privilege of being able to attend to the organ in these hopefully more conservation-enlightened days. Watch these columns c.2088!

From The Revd. Canon Anne Wentzel, Rector of St John’s Mudgee

The Rededication of the Brindley and Foster Organ at St John’s Anglican Church, Mudgee will be another historic event for both the church and the town. Historic for the town because Mudgee has a heritage-rich culture as well as history. As a now modern-day ever growing country town it retains the ‘village’ ambience alongside and complementing the increasing supermarket and mall way of life. Across the town centre lie many beautiful historic churches.

The restoring of St John’s organ will keep the door open to that sacred music which is part of the church’s history worldwide. The organ is of such quality that organists are already seeking to come to Mudgee to play it. Yes, it is one of God’s gifts to us and “a pearl of great price”.

The parish is indebted to the wonderful community of Mudgee and friends from far and wide who have supported the restoration of such a fine instrument. Now we are able to give thanks with concerts of all kinds with that music of such great quality to which only an organ can lend itself.

Its rededication begins with a team of New South Wales’ best organists: our own Gavin Tipping, Peter Jewkes – organist from Christ Church St Laurence and The Revd Michael Deasey, Precentor at the cathedral in Bathurst.

On Sunday 31 August, after the rededication by the Right Revd Richard Hurford, OAM, Bishop of Bathurst at a 9.30 am formal service, All Saints Cathedral Choir, Bathurst will join us for a special Choral Evensong at 2 pm to which all are invited.

The present Rector took up her appointment at St John’s Church during the week in which the organ was being packed and removed to Sydney for restoration, and thus had to cope with six organbuilders on site, as well as the rigours of moving house. Prior to her arrival at Mudgee, she served as Precentor of St Paul’s Cathedral, Melbourne, so has a wide experience of organ and choral music. By remarkable coincidence, prior to that, she was a teacher at Trinity Grammar School where she knew the Jewkes firm’s Rodney Ford as a French student, and a parishioner at St James’ King Street, Sydney, where she knew Peter Jewkes as organist. The clergy it seems, also move in mysterious ways!

The specification is:

| Great Double Diapason Open Diapason Hohl Flute Principal Twelfth Harmonic Piccolo Mixture Trumpet Swell Lieblich Bourdon Open Diapason Gamba Vox Angelica Salicet Mixture Oboe Cornopean Tremulant Choir Lieblich Gedact Dulciana Harmonic Flute Clarionet Pedal Major Bass Sub Bass Principal Bass Flute Bass Couplers Swell to Great Swell to Choir Great to Pedal Swell to Pedal Choir to Pedal |

16 8 8 4 2-2/3 2 III 8 16 8 8 8 4 III 8 8 8 8 4 8 16 16 8 8 |

stopped wood-bass, stopped metal treble 1 - 19 stopped wood, 20 - 58 open metal 15.19.22 stopped wood bass, stopped metal treble stopped wood bass, metal treble bass grooved from Diapason independent stopped wood bass, metal treble 15.19.22 1 - 19 Stopped wood, 20 - 58 stopped metal bass from Gedact 1 - 12 stopped wood, 13 - 19 open metal, 20 - 58 harmonic 1 - 12 open wood, 13 - 30 open metal stopped wood from Major Bass from Sub Bass |

Compass 58/30

Mechanical action throughout [5]

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

[1] Rushworth, Historic Organs, pp. 226-27.

[2] ibid., 227

[3] Notes suplied by David Kinsela to Kelvin Hastie, 1979.

[4] John Stiller, Documenation of Pipe Organ built by Brindley & Foster 1881 - St John the Baptist Anglican Church, Mudgee NSW. (OHTA, 1981), 2-3.

[5] Stiller, op.cit.,4.

TB 1990

Grant to restore organ

By DIANE SIMMONDS

The Mudgee Guardian

Friday, 2 June 2006

St John's Anglican Church has received a heritage grant of $50,000 to restore its 1881 Brindley and Forster pipe organ and to continue conservation work on the church.

NSW Minister for Planning, Frank Sartor, said the grant would help with restoration and conservation work at the landmark gothic revival building. Joint rectors Rev Phillip Gill and Rev Jenny Inglis thanked Mr Sartor and the Heritage Incentive Program for the grant. "The organ and the building enrich community life," they said. The ministers said the church and organ are enjoyed by the whole community. The church is open every day for quiet reflection and there are weddings, baptisms and funerals, concerts and parish worship.

Rev Gill and coordinator of the appeal, Barbara Hickson, said the Mudgee church community had raised around $50,000, which was matched dollar for dollar in the heritage grant, but there is still the need for another $50,000 to be raised. Rev Gill said the church would shortly launch an appeal where the public could sponsor one of the 1,600 pipes in the organ.

However, in the meantime, work on the church has already begun with the 1881 steel cast bell from Sheffield repaired, and further work will continue in the next couple of months on painting and rendering outside the building. Ms Hickson said the organ restoration would begin when the rest of the money was raised, hopefully in six to nine months time, because the restoration would be a complete overhaul of the organ, with the organ completely dismantled.

Ms Hickson said conservation restorer, Peter Jewkes from Sydney would restore the organ.

Photo: TB